Is Trump About to "Abandon" Taiwan, Too?

Three historical junctures when Washington nearly walked away from Taiwan

In one of his whimsical remarks, Donald Trump lately described Taiwan as a “source of pride” for the Chinese leader and went on to say: “He considers it to be a part of China, and that’s up to him, what he’s going to be doing.” This comment, appearing in an interview with The New York Times, seemed to imply that the United States might be willing to walk away from its “commitment” to “defending” Taiwan.

It came out as a stark turn of events, as the United States just approved the largest arms sale to Taiwan in history less than a month ago, to which Beijing swiftly responded by conducting a Taiwan-encircling military drill that pushed the exercise areas closer to the island than ever before.

It is unclear whether Trump has realized that Taiwan no longer figures prominently in the strategic formula laid out under the “Donroe Doctrine,” or whether he was instead hoping to gain leverage in tariff negotiations with Taiwan (on January 12, The New York Times unexpectedly reported that the Trump administration is nearing a trade deal with Taiwan). In any case, his remarks have once again sparked speculation about a renewed “abandoning Taiwan” line in Washington.

Many assume that the United States and Taiwan have long been strategically and ideologically synchronized. Not true. Washington and Taipei have been through some rough patches ever since Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, soundly defeated in China’s civil war, dragged his demoralized Nationalist forces to the island in 1949. Within the U.S. government and the American strategic community, calls to “abandon Taiwan” have repeatedly surfaced.

First Wave: After the “Loss of China”

The first wave of “abandoning Taiwan” debates emerged between 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War. Policy arguments over whether to deploy troops to Taiwan to “save the Nationalists” unfolded both within the U.S. administration and between the executive branch and Congress. In 1949, the U.S. government lost confidence in the Nationalist regime, which had suffered repeated defeats in the face of Communist forces. In a memorandum to the National Security Council dated August 4, 1949, Secretary of State Dean Acheson explicitly argued that the Nationalist authorities were corrupt and incompetent, that the “fall” of Taiwan was inevitable, and that the State Department had ruled out the possibility of using U.S. forces to “defend” the island.

On October 6, 1949, the U.S. State Department, in a report for consideration of the National Security Council, argued that if U.S. forces were used to “defend” Taiwan, this would only strengthen nationalist forces on the Chinese mainland and thereby endanger U.S. interests throughout Asia.

In late December 1949, the National Security Council formally adopted the State Department’s position and decided against taking military action to “assist” Taiwan. On January 5, 1950, President Truman issued a public statement saying that, in keeping with the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Proclamation, Taiwan was surrendered to Chiang Kai-shek, and for the past four years the United States and other Allied Powers had accepted the exercise of Chinese authority over the island.

Truman further declared:

“The United States has no predatory designs on Formosa, or on any other Chinese territory. The United States has no desire to obtain special rights or privileges, or to establish military bases on Formosa at this time. Nor does it have any intention of utilizing its Armed Forces to interfere in the present situation. The United States Government will not pursue a course which will lead to involvement in the civil conflict in China.”

“Similarly, the United States Government will not provide military aid or advice to Chinese forces on Formosa. In the view of the United States Government, the resources on Formosa are adequate to enable them to obtain the items which they might consider necessary for the defense of the island.”

Subsequently in 1950, with the outbreak of the Korean War, where “Red China” and the United States confronted each other directly on the battlefield, and the rise of McCarthyism featured by massive anti-leftist political persecution, the U.S. government started to view Taiwan through a different lens. Taiwan came to be regarded as a Western bridgehead in the Asian theater of the Cold War to contain the “red fever,” and Washington advanced the so-called “undetermined status of Taiwan.” From that point on, calls to “defend” Taiwan became the dominant view both inside and outside the U.S. government.

Second Wave: Nixon’s Grand Realignment

The second wave of “abandoning Taiwan” debates emerged in the mid- to late 1960s. As the U.S.-China-Soviet triangular relations began to shift, the strategic idea of aligning with China to balance the Soviet Union gained traction in Washington, and policymakers started to re-examine the containment policy toward China that had lasted more than a decade.

The 136 Sino-U.S. ambassadorial talks held between 1955 and 1970 made Washington keenly aware that the Taiwan question was a precondition for any attempt to ease relations with China. For instance, in the early 1960s, when Chiang Kai-shek was actively plotting to launch a counteroffensive against the mainland, the Chinese representative stated clearly during the Warsaw talks that the day Chiang attacked the mainland would be the day the Chinese people liberated Taiwan. In the end, the U.S. side explicitly indicated that if Chiang Kai-shek attempted to take action, Beijing and Washington would join together to stop him.

In 1966, James W. Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, held a hearing on China policy in which he sharply criticized the existing U.S. foreign policy as being seriously out of touch with international reality. When addressing the China question, he argued that in fact there were not “two Chinas,” but only one--the Chinese mainland.

In July 1971, during his talks with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger stated that the United States did not support “two Chinas” or “one China, one Taiwan” as solutions for Taiwan’s political future, and that once the United States withdrew its forces, Taiwan would have no choice but to accept some form of unification.

Chiang Kai-shek himself had a clear understanding of this. In his diary in early 1970, he wrote:

“America’s sinister scheme toward China, the so-called ‘one China, one Taiwan’ policy--the ‘one Taiwan’ they speak of is meant to create a Taiwan of ‘Taiwanese,’ not a Taiwan of the Republic of China. This is clear proof that they will not be satisfied until our state is destroyed.”

In 1972, during President Nixon’s visit to China, the United States once again reaffirmed its position that it recognizes there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of China. Washington stated that it would no longer advance the notion that Taiwan’s status is undetermined and would not support “Taiwan independence.”

The Shanghai Communiqué, signed during Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, provided the framework of the U.S. “one China policy.” In the communiqué, the U.S. side declared:

“The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position. It reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves.”

This wording reflects a kind of diplomatic wisdom in which Beijing and Washington “seek common ground while reserving differences. However, the U.S. has later on sought to blur the one-China principle by placing emphasis on the particular meaning of the word “acknowledges.”

But it is worth noting that in 1980, the United States abolished the “Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty” signed between Washington and Taipei in 1954. The treaty stipulated:

“Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the West Pacific Area directed against the territories of either of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.”

Washington’s Taiwan Relations Act in 1979, enacted to replace the “mutual defense treaty”, says it is the policy of the U.S. “to consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.”

In the legal sense, Washington had already abandoned a formal defense commitment to Taiwan, while carefully preserving a posture of strategic ambiguity. What it chose to keep was not a binding security guarantee, but a flexible instrument of leverage in its broader China policy.

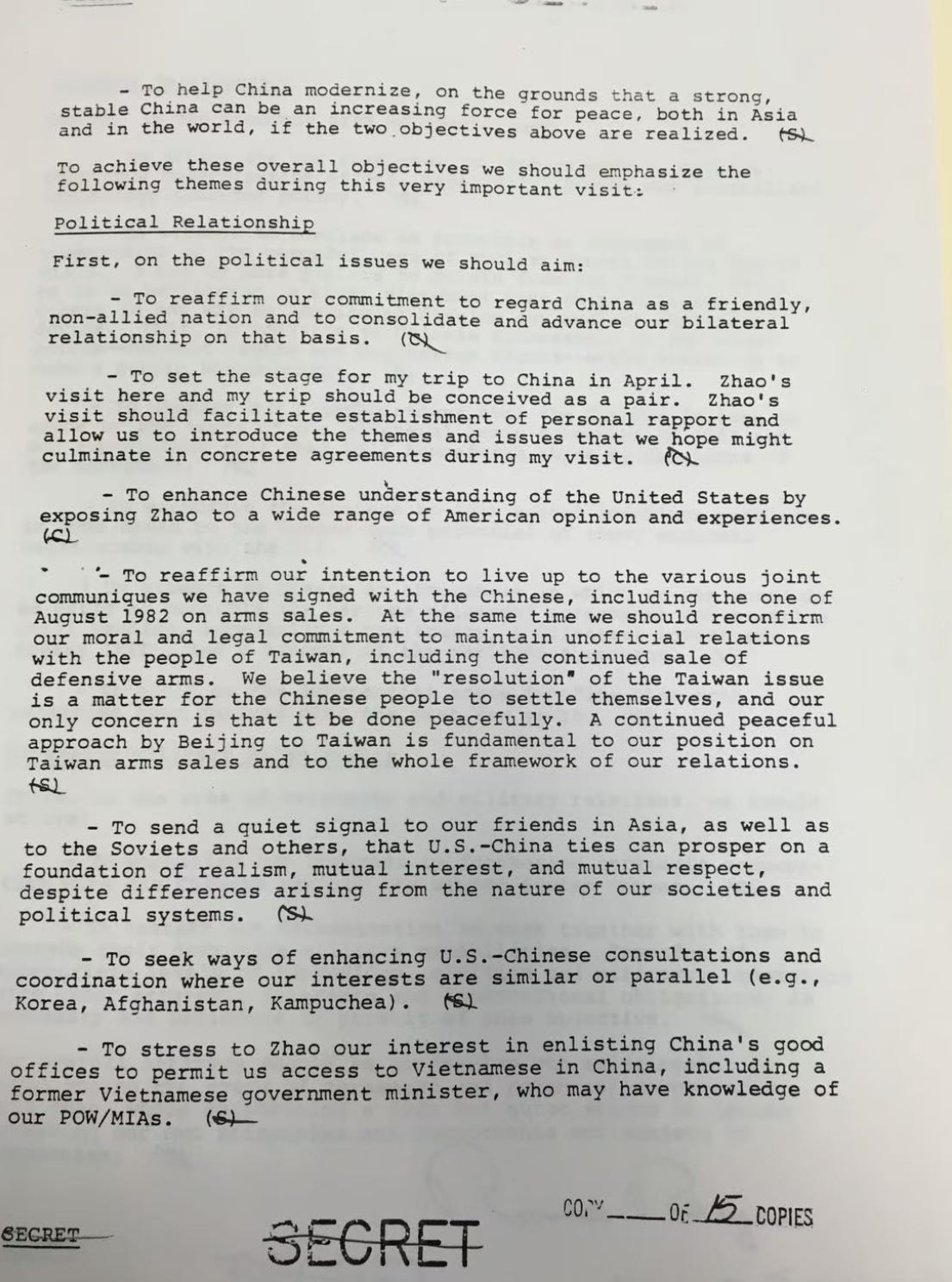

In declassified White House documents at the Reagan Presidential Library, President Reagan instructed his cabinet members to strictly abide by the joint communiqués between China and the United States. When an envoy acting as intermediaries for then-Taiwan leader Chiang Ching-kuo repeatedly extended “olive branches,” Reagan and his staff were extremely cautious, turning down multiple requests for meetings. Even in correspondence with Chiang, messages were often delivered only orally, and Reagan ordered that no hard copies of those oral messages be left in Chiang’s possession.

Third Wave: The Last China-U.S. Honeymoon

The third wave of “abandoning Taiwan” debates began in the early 21st century. China’s accession to the WTO, the outbreak of the Afghanistan War, and Washington’s unprecedented focus on the global war on terror led the United States to view China as more of a partner than a strategic rival for nearly a decade. As China-U.S. relations entered a “honeymoon period,” some figures in the American strategic community, working from the assumptions that China-U.S. cooperation would continue to deepen and that cross-Strait unification was an unstoppable trend, argued that the United States should “discard” Taiwan, which they saw as a burden hampering further improvement in relations with Beijing.

In November 2009, retired Admiral Bill Owens, former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wrote that in dealing with China, the United States should abandon a posture of hedging, competition, and suspicion, and instead choose cooperation, openness, and trust. To that end, he argued, Washington needed to reassess the Taiwan Relations Act, a piece of outdated legislation that provides the legal basis for continued arms sales to Taiwan, and that ending such arms sales could open new space for the development of China-U.S. relations.

Charles Glaser, a professor at George Washington University, argued that abandoning its commitment to Taiwan would remove the most obvious and most contentious flashpoint in China-U.S. relations and pave the way for sustained improvement over the coming decades. Charles Freeman, a senior American diplomat who once served as Nixon’s translator during the 1972 visit to Beijing, similarly stated in multiple presentations that as cross-Strait relations gradually eased and cooperation deepened, the prospect of peaceful unification was becoming more likely, and that the United States, in pursuit of its long-term strategic interests, should view this trend rationally and begin to accept it.

Similar notions continued to circulate in Washington, repeatedly challenging the mainstream position that favored maintaining the status quo. This round of policy debate, triggered by the “abandoning Taiwan,” failed to dislodge the dominance of the status quo camp within the U.S. policy community on cross-Strait issues. Nonetheless, it contributed a degree of rational and pragmatic reflection that informed the Obama administration’s approach to the Taiwan Strait.

Toward the Fourth Wave?

In December 2016, then U.S. President-elect Donald Trump held a phone call with Taiwan leader Tsai Ing-wen, who extended his “congratulations.” Trump was thereby regarded as the first U.S. president or president-elect since 1979 to speak directly with a Taiwan leader, a move that immediately drew ire from Beijing.

In May 2020, as Tsai began her second term as the leader of the Taiwan authorities, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo bluntly issued a public statement congratulating her and explicitly referring to her as the “President of Taiwan,” setting a dangerous precedent again. In May 2024, under the Biden administration, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken released a similar statement.

This series of actions by the U.S. not only went against the commitments Washington made in the China-U.S. Joint Communiqués, but also, against the backdrop of the international community’s broad adherence to the one-China framework, repeatedly sent misleading political signals to pro-independence cliques in the Taiwan authorities.

These moves emboldened separatist forces on the island and heightened the risk of strategic miscalculation. Taking advantage of such signals, the Taiwan authorities controlled by the pro-independent DPP continued to push forward an incremental independence agenda and political provocations, leading to the rapid deterioration of cross-Strait relations. The tensions were then reversed and portrayed as evidence that the mainland was changing the status quo or strengthening military options, driving the Taiwan Strait into a classic spiral of external interference, escalating provocation, and growing security instability.

In 2021, Admiral Philip Scot Davidson, commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command, said at the Congress that Taiwan is clearly one of China’s ambitions, and “the threat is manifest during this decade, in fact, in the next six years.” The “Davidson Window” that implies Beijing's becoming capable of developing sufficient capabilities to take control of Taiwan was heavily hyped. In 2022, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s opportunistic visit to Taiwan pushed “protecting Taiwan” sentiment in the United States to a new peak.

Despite the rising great-power tensions, the logic of “abandoning Taiwan” started to gain ground in light of the new developments of events.

Multiple war games conducted by American think tanks indicated that the United States would suffer heavy losses in the event of a Taiwan Strait conflict. This prompted senior American policymakers to become increasingly aware of the risks involved.

In January 2024, President Biden explicitly stated that “the United States does not support the independence of Taiwan.” Trump’s recent remarks are highly likely to reflect a pragmatic and transactional approach toward the Taiwan issue, and may also signal the emergence of a fourth wave of discourse in the U.S. advocating the abandonment of Taiwan.

A few scholars also began to warn against the risks of strategic miscalculation and a crisis spiral between China and the United States. They began to raise more sober questions, such as whether a “mainland attack on Taiwan” is really that imminent, and whether Taiwan genuinely involves U.S. core interests, and whether the American public is actually prepared for a war with China.

Senior fellow of the Quincy Institute, Michael Swaine, and RAND Corporation political scientist, Michael Mazarr, are the main representatives of this latest wave of such thinking. Their core proposal is gradual disengagement from Taiwan. They stress that Taiwan is not a core U.S. interest; American policy, as they argue, should shift its focus toward deterring independence.

In a September 2025 report titled “Taiwan: An Important but Non-Vital U.S. Interest”, Swaine offers a sober reassessment of Taiwan’s value to the United States from four perspectives: strategic value, economic value, credibility trap, and moral argument. He criticizes the rationales long used in the U.S. strategic community to justify playing the Taiwan card. Swaine asserts that Taiwan is an important but not vital U.S. interest. It is not an interest that justifies the United States going to war with China to defend.

Doug Bandow, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, also contends that while occupying Taiwan would help advance the mainland’s military capabilities, it would not fundamentally alter America’s overall strategic position. The greatest danger facing the United States is war itself, not the mainland’s “takeover” of Taiwan.

From Truman’s era of no U.S. troops stationed in Taiwan, to the Cold War peak of “defending Taiwan,” and then to the cyclical waves of debate over “abandoning Taiwan,” U.S. policy toward Taiwan has never been rooted in a sincere commitment. There have always been good reasons for this approach, as policy has oscillated between realist calculation and ideological rhetoric. President Trump’s recent remarks merely brought into the open what previous administrations preferred to keep behind closed doors: the United States owes no security obligation to Taiwan.

Zhai Xiang works as a research fellow with the Xinhua Institute on China-U.S. relations.

Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a senior journalist with Xinhua News Agency.

Frankly, given that American AI companies are racing toward super-capable uncontrollable misaligned AI, getting NVIDIA’s chips out of US hands buys everyone on Earth more time to confront and prepare for this incredible technological disruption and hopefully begin to act sanely about its development and rollout so that we can avoid catastrophe and avoid handing over our agency and control of our society to minds that are not currently capable of being aligned to human values.

More from the state propaganda agency staff officers, employed to spread the regime's words here on this platform. Such is Substack.

Paving the way for the invasion and the post-invasion concentration camps planned for democratic Taiwan's population.