Takaichi's Taiwan Remarks in Perspective

Revisiting "four political documents" that underpin China-Japan relations

After decades of eventful engagement, Chinese are hardly surprised by the showmanship and fickleness long embedded in Western politics. In addition to the latest round of mixed signals sent toward Beijing by U.S. President Donald Trump and his high commissioner on trade war Scott Bessent, Japan is also staging its own version of political flip-flops.

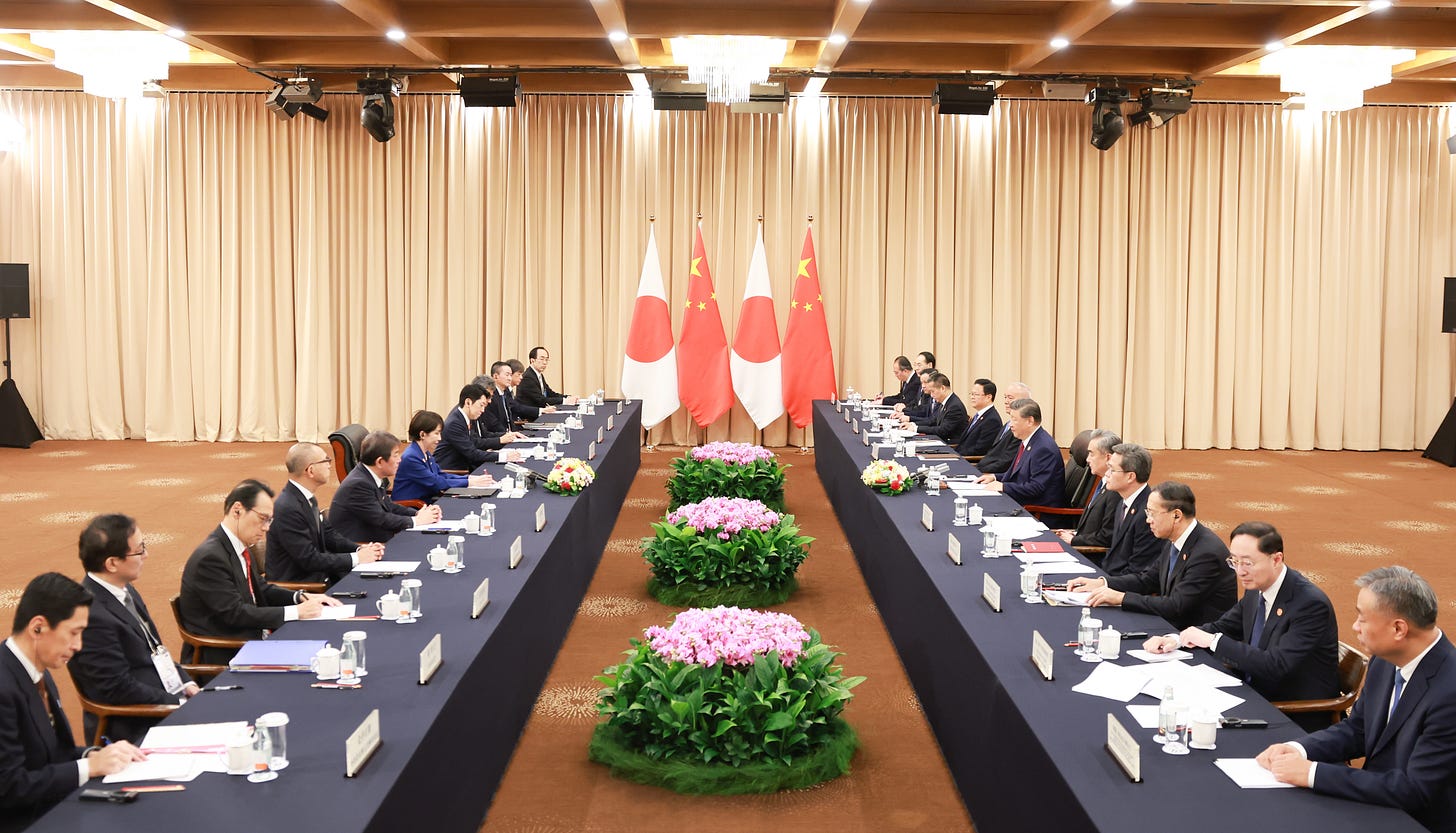

On October 31, on the sidelines of the APEC South Korea summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping met, at Japan’s request, with Japan’s newly elected prime minister Sanae Takaichi. The first-ever meeting between the two leaders was supposed to kick off a good start for the bilateral high-level exchange and stabilize relations in East Asia. However, that same evening, Takaichi tweeted on X: “Before the APEC summit, I greeted and spoke with Lin Hsin-yi, ‘Senior Adviser to Taiwan’s Office of the President.’”

Her use of that title, unsurprisingly, drew ire from China, whose foreign ministry protested that Takaichi had gone against the “four political documents” that were deemed as the foundation of China-Japan relations. Beijing has long adhered to a stance on the Taiwan question reminiscent of the Hallstein Doctrine, viewing the island as a province and declining diplomatic ties with any country that recognizes Taiwan’s self-claimed sovereignty. By applying the word “president” in Lin’s title, Japan’s first female prime minister, who appeared eager to push charm offenses across the APEC venue, seemed to have engaged in a political provocation in the eyes of Beijing, which just commemorated the 80th anniversary of Taiwan’s restoration a week earlier.

In response to China’s protest, on November 4, Japan’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Toshimitsu Motegi stated:

“APEC consists of 21 economies, and on such multilateral occasions, meetings between the Japanese Prime Minister and representatives from the Taiwan side have taken place many times in the past. I believe this meeting was consistent with past practice. This conversation between Prime Minister Takaichi and Lin Hsin-yi was conducted on the basis of the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communique and in the form of non-governmental and pragmatic exchanges to maintain relations with Taiwan. The Japanese government does not believe this act violated its longstanding position. As I just mentioned, during past APEC leaders’ meetings, Japan has met with Taiwan representatives multiple times. After this meeting, China lodged a representation with Japan, but Japan reiterated its own position and issued a rebuttal. In any case, Japan’s basic policy on the Taiwan question has not changed in any way.”

It was surely not Japan’s unofficial exchanges with the Taiwan region that incurred Beijing’s wrath. However, referring to the Taiwan representative with terms implying a sovereign status clearly crosses the line of non-governmental interaction and ventures into political symbolism.

Adding fuel to the fire, on November 7, Takaichi asserted that a military emergency in Taiwan could constitute a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan under the country’s security laws. This caused an even greater response from Beijing, which criticized her move that “grossly interfered in China’s internal affairs.”

During the meeting with Takaichi on October 31, Xi Jinping explicitly emphasized that both sides should uphold the political foundation of bilateral relations in accordance with the principles and direction established in the “four political documents.” Takaichi responded on the spot: “On the Taiwan question, Japan will adhere to the position stated in the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communique.” Yet, her follow-up acts reduced that pledge to mere words.

Many readers may not be familiar with the concept of the “four political documents” between China and Japan. They constitute the core framework that defines the political basis and principles of China–Japan relations: 1972 Joint Communique, 1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, 1998 Joint Declaration, and 2008 Joint Statement.

It is worth noting that honoring the “four political documents” has never been a unilateral demand from China. It is a commitment repeatedly affirmed by successive Japanese leaders in public.

On November 15, 2024, during President Xi’s meeting with Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba in Lima, Ishiba stated that “Japan adheres to the principles and consensus established in the ‘four political documents’ between Japan and China.”

On November 16, 2023, when Xi Jinping met Prime Minister Fumio Kishida in San Francisco, the two leaders reaffirmed their commitment to the principles and consensus of the “four political documents.”

Even Shinzo Abe, regarded by Takaichi as her political mentor, stated in Beijing on October 26, 2018, that “guided by the spirit of mutual benefit and non-threat, the two sides should advance bilateral relations based on the consensus confirmed in the ‘four political documents.’”

So, how do these “four political documents,” repeatedly mentioned and affirmed by leaders of both countries, address the roles of the two countries regarding the Taiwan question?

1. Joint Communique of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People’s Republic of China (1972)

“The Government of the pepole’s Republic of China reiterates that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the PRC. The Government of Japan fully understands and respects this position held by the Government of China, and reaffirms its commitment to observe the position stated in Article 8 of the Potsdam Proclamation.”

In the statement, the Japanese government declares its adherence to Article 8 of the Potsdam Declaration, which states that “the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out.”

The Cairo Declaration of 1943, jointly issued by the major Allied leaders, explicitly stipulated:

“All the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China.”

Under international law, states, not governments, are the subjects of sovereignty. Governments merely represent the state. After 1949, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) replaced the Republic of China (ROC) and succeeded to its corresponding rights and obligations. This was also unequivocally affirmed by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758:

“Recognizing that the representatives of the Government of the People’s Republic of China are the only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations and that the People’s Republic of China is one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.”

Therefore, Japan’s statement that it adheres to Article 8 of the Potsdam Declaration is, in effect, confirmation that Taiwan belongs to China, and indirectly confirms that Taiwan falls within the sovereignty of the PRC.

Backgrounder: In February 1972, U.S. President Richard Nixon visited China on an ice-breaking surprise tour, achieving an unlikely detente that reversed the Cold War’s great game and astonished the world. This development sent shock waves through Japanese politics, which at the time followed a “pro-U.S., pro-Taiwan” policy line. With the United States shifting its diplomatic priorities, calls grew rapidly inside Japan to reassess its China policy. Prime Minister Eisaku Sato was forced to step down, and Kakuei Tanaka, who pledged to normalize diplomatic relations with the PRC, became the new prime minister. In September of the same year, Tanaka visited Beijing, where the leaders and foreign policy officials of both countries signed this Joint Communique.

2. Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the PRC and Japan (1978)

“The PRC and Japan express their satisfaction that, since the Joint Communique of the Government of the PRC and the Government of Japan was issued in Beijing on September 29, 1972…They confirm that the above-mentioned Joint Communique constitutes the foundation of the relations of peace and friendship between the two countries, and that all the principles set forth in the Joint Communique shall be strictly observed.”

“The contracting parties shall develop lasting relations of peace and friendship between the two countries on the basis of the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.”

In this context, Japan had already confirmed in the 1972 Joint Communique that Taiwan is part of China. In the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Japan further committed to respecting China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. These two documents therefore form a logically consistent and legally coherent framework, within which Japan effectively affirms that Taiwan is part of China’s territory.

Backgrounder: Based on the 1972 China–Japan Joint Communique, the two countries held multiple rounds of negotiations and eventually signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in Beijing in August 1978. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China, as well as both the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors of Japan, ratified the treaty respectively. On October 22, 1978, Deng Xiaoping, then Vice Premier of the State Council, paid an official goodwill visit to Japan, marking the first visit to Japan by a Chinese state leader since the founding of the PRC. The following day, the instruments of ratification were exchanged at the Prime Minister’s Office in Tokyo, with Deng and Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda attending the ceremony. After the exchange of ratification documents by the foreign affairs ministers of both countries, the treaty officially entered into force.

“Japan will continue to adhere to the position on the Taiwan question as stated in the China–Japan Joint Communique, reaffirming that there is only one China. Japan will maintain only non-official and regional-level relations with Taiwan.”

This declaration, in essence, reconfirmed the political commitment made in the 1972 Joint Communique. Japan voluntarily reaffirmed that commitment and pledged not to develop any form of official relations with Taiwan, nor indirectly recognize it as a “country.”

However, by referring to Taiwan representatives as holding titles such as the “Senior Adviser to Taiwan’s Office of the President” in multilateral settings, Takaichi undoubtedly crossed the boundary of “non-official interactions,” in direct contradiction to Japan’s stated political commitment.

Backgrounder: At the invitation of the Japanese government, then Chinese President Jiang Zemin paid a state visit to Japan in November 1998, the first state visit to Japan by a Chinese head of state since the founding of the PRC, coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the signing of the peace treaty. Jiang and Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi, guided by the principle of “taking history as a mirror and facing the future,” reviewed both the positive and negative experiences and lessons in the development of China–Japan relations and ultimately issued this Joint Declaration.

“Both sides reaffirm that the Joint Communique of September 29, 1972, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of August 12, 1978, and the Joint Declaration of November 26, 1998 constitute the political foundation for the stable development of China–Japan relations and for opening up the future. The two sides confirm that they will continue to abide by the principles of the three documents.”

“The Japanese side reiterates that it will continue to adhere to the position on the Taiwan question as stated in the 1972 Joint Communique.”

The phrase “constitute the political foundation” is highly significant.

It implies that if Japan violates the principles set out in these documents, such as the position that Taiwan is part of China and Japan does not maintain official relations with Taiwan, it is essentially undermining the very foundation of China-Japan relations.

Backgrounder: In the early 2000s, China-Japan relations deteriorated due to issues including visits by Japanese leaders to the Yasukuni Shrine. After Japanese leaders began seeking to repair bilateral ties, then Chinese President Hu Jintao visited Japan in May 2008. This “spring thaw” visit marked a transition from ice-breaking to strategic mutual benefit. During the visit, Hu and Fukuda signed this Joint Statement in Tokyo.

Since the late 19th century, when China was forced to cede Taiwan, Japan subjected the island to colonial rule for half a century, which in many ways added to the enduring complexity of today’s Taiwan question. While China has never expected Japanese politicians to demonstrate the same kind of dignity and courage as West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s “Kniefall von Warschau,” the repeated disregard or lack of deep comprehension of the “four political documents,” repeatedly confirmed by the leaders of both countries, continues to create practical obstacles to the steady development of China-Japan relations.

Failing to honor international documents does little to bolster Japan’s self-vaulted image of the upholder of “rules-based international order.” Moreover, attempting to use its former colony as a geopolitical pawn against a neighboring Asian country neither advances Japan’s long-sought “normal state status” nor serves Takaichi’s ambition to see Japanese diplomacy “blossoming on the world stage.”

Zhai Xiang works as a research fellow with the Xinhua Institute on China-U.S. relations.

Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a journalist with Xinhua News Agency.