Ryukyu Question: A Sovereignty Issue Deferred

As encounters between Chinese and Japanese military aircraft on the high seas near Okinawa emerged as the real-life reflection of the two countries’ mounting diplomatic tensions, Okinawa itself became a new focus of bilateral disputes.

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has made provocative remarks on Taiwan by flirting with the possibility of Japanese military intervention, and further claimed on November 26 that, according to the Treaty of San Francisco, Japan is “not in a position to recognize Taiwan’s legal status.” In response, some Chinese officials and media outlets appear to have revived the argument that the status of Okinawa, known historically as “Ryukyu,” remains undetermined.

In November, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs posted on Twitter some contents related to the Potsdam Proclamation concerning the Allied definition of Japan’s postwar territorial scope, which was widely interpreted as hinting at this position. If that signal was not explicit enough, on November 28, China News Service, the country’s second-largest state news agency, published an article titled “It Is Time to Settle the Old Account of Ryukyu’s Sovereignty,” openly questioning the sovereignty of Okinawa. Unsurprisingly, this triggered widespread attention both inside and outside China regarding the future direction of Sino-Japanese relations.

Such countermeasures are not without precedent. In 2012, the Japanese government’s so-called “nationalization” of the Diaoyu Islands (or “Senkaku Islands” called by the Japanese) plunged Sino-Japanese relations to a low point. In May 2013, People’s Daily published an article arguing that, according to the postwar arrangements for Japan stipulated in the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation, not only Taiwan and its affiliated islands (including the Diaoyu Islands) and the Penghu Islands should be returned to China, but that the historically unresolved Ryukyu question had also reached a point where it could be revisited.

So, how did Ryukyu, once a vassal state of China, come under Japan’s subjugation and become Okinawa? What arrangements did the Allies make regarding Ryukyu’s future during WWII? How did the indigenous people of Ryukyu view Japan and China after the war?

The Ryukyus are a chain of volcanic islands that stretch southwest from Japan’s Kyushu to China’s Taiwan. Historically, their Chinese name was long identical to that used for Taiwan. Once a tributary state of China, the Ryukyu Kingdom’s status changed after the 1609 invasion by Shimazu Tadatsune, a Japanese daimyo based in southern Kyushu. The islands started paying additional tribute to the Shimazu clan. The Shimazu domain profited substantially by leveraging Ryukyu’s tributary trade with China, extracting significant economic benefits from this intermediary position. These revenues strengthened the Shimazu clan considerably and later contributed to its key role in the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and Japan’s drive toward Westernization in the late 1860s.

From 1609 until the 1870s, the Ryukyu Kingdom existed simultaneously as a tributary state of both China and Japan. Its official documents continued to be written in Chinese, its court attire followed Chinese styles, and even the 1854 Treaty of Amity between the United States and Ryukyu was signed solely in English and Chinese. However, this subtle balance, which had lasted for more than two centuries, was disrupted by Japan’s rapid rise following the Meiji Restoration. In 1874, Japan transferred administrative authority over Ryukyu from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Ministry of Home Affairs; by 1879, Japan formally annexed the kingdom and reorganized it as Okinawa Prefecture.

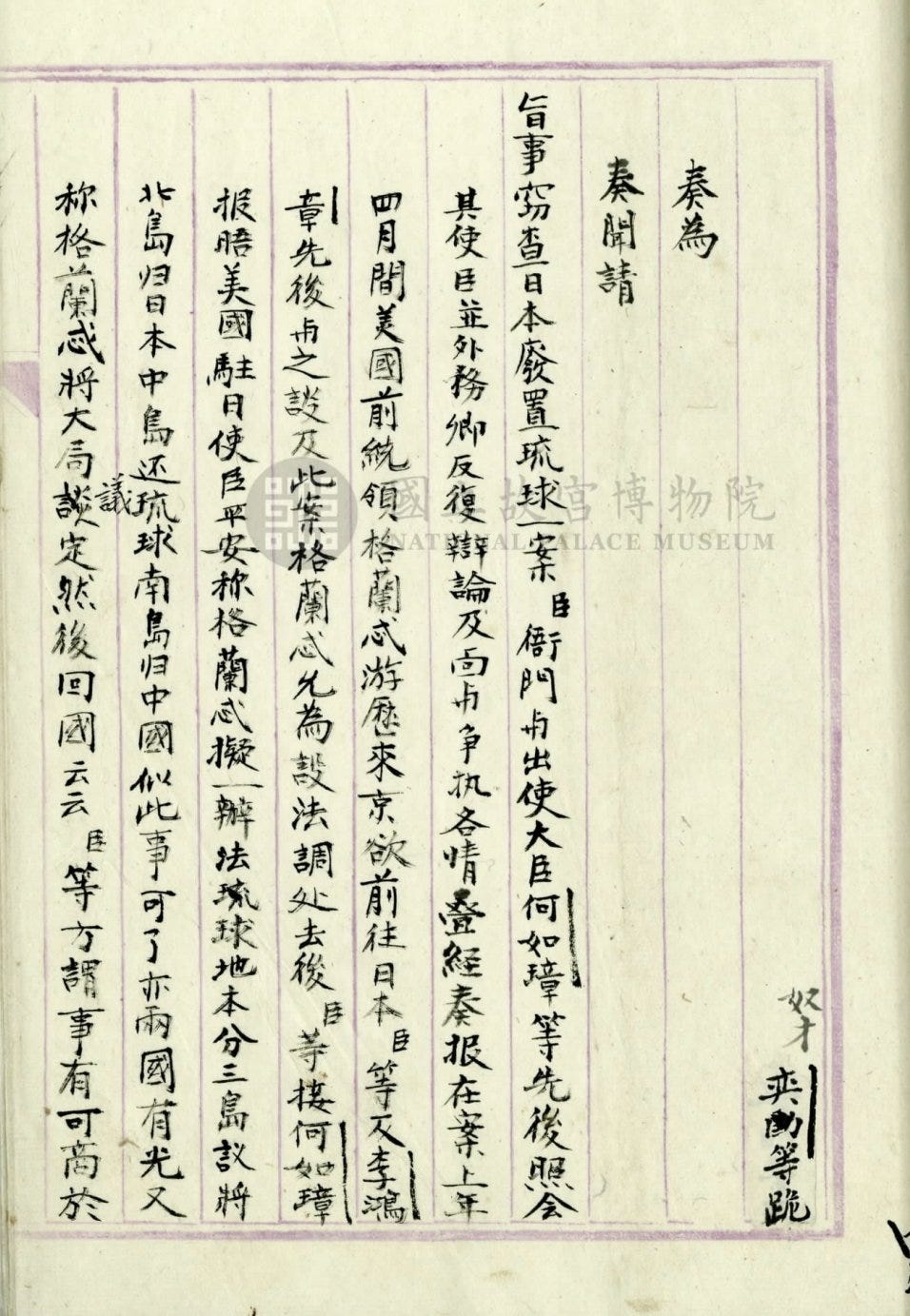

Seized with panic, China reached out to the former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, who was on a tour around the world, wishing to resolve the question through his arbitration. Having visited Beijing and Tokyo, Grant quickly devised a proposal to China, with the northern part ceded to Japan, the southern part to China, and the rest restored to the previous kingdom. On April 17, 1880, the Japanese government raised the proposal to divide the Ryukyus in two, with the Miyako-jima (宫古岛) and Yaeyama Islands (八重山群岛) put under the rule of China. On October 28, 1880, the Chinese government accepted the proposal, and agreed to grant Japan most-favored nation status in reciprocity. However, China and Japan never implemented this agreement, and the issue of the Ryukyu Islands remained unresolved, with Japan continuing to control the islands until the end of World War II.

Despite rarely mentioning this question since the Japanese annexation of the Ryukyus, successive Chinese administrations have never officially recognized Japanese sovereignty over these islands, nor have they relinquished their proper rights to the Ryukyus.

Chiang Kai-shek, China’s supreme leader from the late 1920s to 1949, despite carrying much historical controversy, did not recognize Japan’s control over the Ryukyu Islands either and attempted to address this question. On September 13, 1932, close to the one-year anniversary of the Mukden Incident in which Japan launched a surprise attack on northeast China under the excuse of a “survival crisis” (sounds familiar?), Chiang wrote in his diary, expectantly, by the Moon’s Festival in 1942, “China should be able to recover Manchuria, liberate Korea, and take back Taiwan and the Ryukyus.”

On a night in late September 1940, Chiang coincidentally reviewed the diary entry written down eight years before. Still, he believed that China had a chance “to recover the Ryukyus.” During a press conference held in early November 1942 in America, T. V. Soong, China’s Foreign Affairs Minister and Chiang’s brother-in-law, indicated that China should take back northeast China, Taiwan, and the Ryukyus, and that Korea had to become independent.

In late November that year, Madame Chiang Soong May-ling left for America. Before her departure, Chiang Kai-shek meticulously prepared her for talks with Roosevelt. The very first point was that Manchuria (aka northeast China), Taiwan, and the Ryukyus should be returned to China, and China would approve of America using naval and air bases at these locations. Having met with FDR, Soong May-ling, on March 1, 1943, informed Chiang in her telegram of Roosevelt’s agreement that “the Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan should be reverted to China in the future.”

Preparing for the Cairo Conference that took place from November 23 to 26, 1943, the Advisory Office of the Military Commission envisioned a comprehensive plan that the Generalissimo would raise during the meeting. According to the draft, Japan should retreat from all the territories that it had occupied since September 18, 1931, and restore to China Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands (aka Penghu Islands), as well as the Ryukyus. The draft even included a flexible back-up plan that Okinawa could either be put under international trusteeship or designated as a demilitarized zone.

However, by November 15, 1943, Chiang apparently had changed his mind. In the entry on that day, Chiang argued that the status in history of the Ryukyus and Taiwan was different: “The Ryukyus as a kingdom resembles Korea in this position,” and, therefore, Chiang decided not to raise the question regarding these islands during the conference.

To Chiang’s surprise, on November 23, Roosevelt took the initiative to bring up the Ryukyu question during his meeting with Chiang. According to the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS):

“The president then referred to the question of the Ryukyu Islands and enquired more than once whether China would want the Ryukyus. The Generalissimo replied that China would be agreeable to joint occupation of the Ryukyus by China and the United States and eventually, joint administration by the two countries under the trusteeship of an international organization.”

Based on Chiang’s diaries, he might have softened on the Ryukyu question for three reasons. First, other lost territories of China, such as Manchuria and Taiwan, weighed more heavily on his heart. Therefore, he chose to focus on what was important to him.

Second, Chiang was concerned about America’s sincerity. Roosevelt’s offer to allow China to take over these islands of such great strategic importance might have sounded too good to be true to Chiang. In addition, Chiang, being diplomatically inexperienced, was suspicious as to whether Roosevelt was testing China’s ambitions on expansionism.

Third, the Ryukyus were a tributary state of China rather than an inherent part of the territory of China, similar to the status of Korea historically. The close historical relations between China and the Ryukyus remained suzerainty ties, while China had never exercised direct control there. Chiang, as one of “the Big Four Leaders” of the Allies, grandly proclaimed that he coveted “no gain” and entertained “no territorial expansion.” Consequently, attempts to incorporate the Ryukyus into Chinese territory seemed inconsistent with Chiang’s moral claims.

On December 1, 1943, the “Three Great Allies” jointly issued the Cairo Declaration that stipulated:

“It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the First World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed.”

The future of the Ryukyus was not mentioned in this document, though the statement that “Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed” implied it did not belong to Japan in the view of the Allies.

At the Tehran Conference of 1943, Stalin told Roosevelt that the Ryukyus, which Japan forcibly annexed in 1879, should be returned to China.

Two years later, at the Potsdam Conference, the four great Allies reached a final decision over the unresolved Japanese territorial issue. With reference to the Cairo document, the Potsdam Declaration defined the limits of the post-war “to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.” However, the Potsdam Declaration that Truman, Churchill, and Stalin issued jointly with the absent Chiang on July 26, 1945, like the Cairo document, made no mention of the islands. But clearly, the future of Okinawa is up to the discretion of the Allies.

As one of the principal victorious powers in the Pacific theater of WWII, China naturally has a legitimate voice on this question.

In October 2025, China’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Sun Lei, publicly urged Japan to “end its discrimination and prejudice against the indigenous people of Okinawa.” Many assumed this was just routine diplomatic language. But in fact, it carries deep, painful historical roots.

After Japan annexed the Ryukyus, for a long while, it never truly treated the Ryukyuan people as part of its “Yamato” nation. In 1904, Japanese anthropologists published “Studies on Human Races,” openly stating that:

“The racial status of the Ryukyuan people is even lower than that of the Taiwan aboriginal.” The justification? Their supposedly “ugly appearance” and “weak physique.”

Even today, reading these words is shocking. It is difficult to see any trace that Ryukyuans were ever regarded as “fellow Japanese.”

By the end of the 1945 Battle of Okinawa, the Japanese military even forced large numbers of Ryukyuans to commit mass suicide. Scholars still debate the exact number, and some estimates go above 100,000. Having spoken with several American veterans who witnessed the battlefield ten years ago, I believe this much is clear: Tens of thousands certainly lost their innocent lives.

As early as 1879, right after Japan forcibly annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom, Ryukyuans traveled to Beijing to plead for China’s help. And after WWII, with Okinawa reduced to ruins, one cannot avoid asking: How would the people of a devastated Ryukyu view Japan after all of this?

The answer lies buried in the archives.

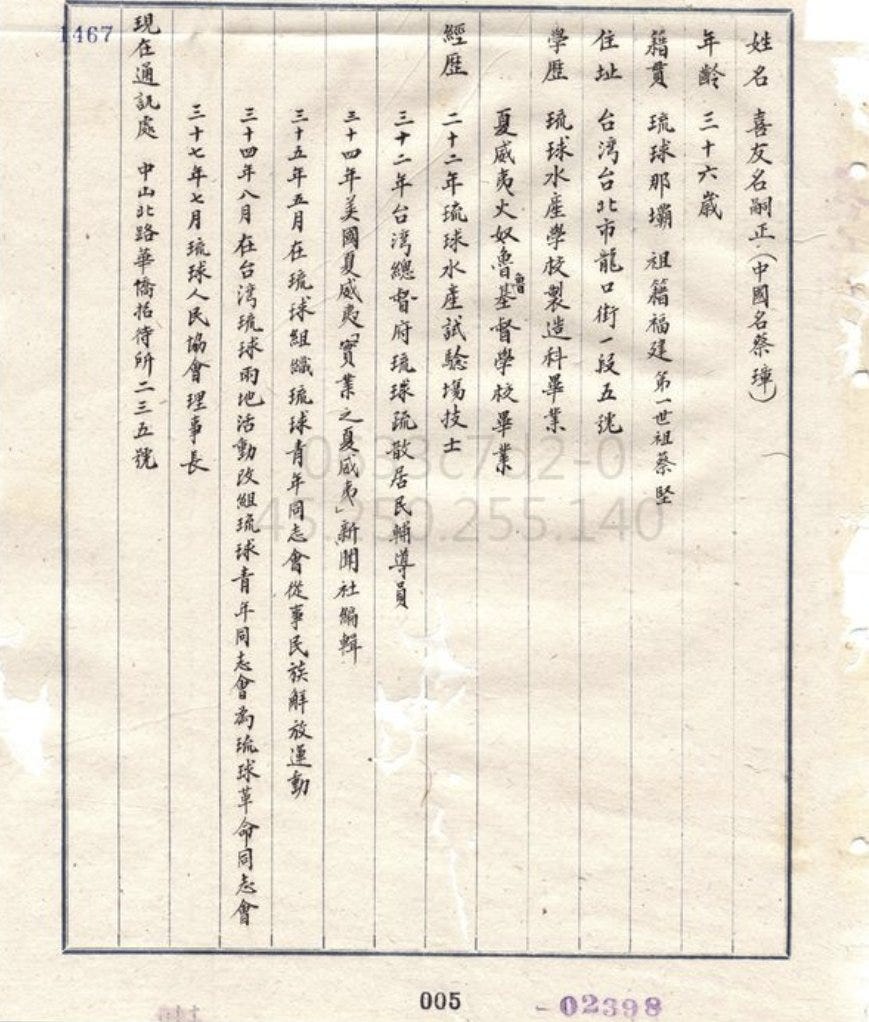

Following Japan’s surrender in 1945, Ryukyu gradually emerged on the agenda and was repeatedly mentioned by China’s senior officials. Chiang Kai-shek, probably overwhelmed with his civil war against the communists, did not discuss the islands in his diaries over the course until 1948. While his approach to Okinawa seemed to have stalemated, the visit to Nanjing during the summer of 1948 by Kiyuna Tsugumasa (he also had a Chinese name: Cai Zhang/蔡璋), head of Okinawa’s “Revolutionary Society (琉球革命同志会),” brought Chiang a new chance to move forward with the question.

Established in the early 1940s, the Ryukyu Revolutionary Society was committed to anti-Japanese activity and clearly demonstrated its pro-China stance. As early as 1946, the Society wrote to Chiang and voiced its loyalty, vowing to subordinate Okinawa to the rule of China. However, Chiang only asked his Foreign Affairs Ministry to “study the matter and report back,” and nothing further happened.

In the autumn of 1947, Kiyuna submitted another petition to Chiang, urging China to direct its diplomats at the upcoming peace conference with Japan to demand that the Ryukyus be incorporated into China’s territory. He wrote that “China and the Ryukyus have maintained relations for over a thousand years; in politics, economics, culture, customs—there is nothing that does not trace back to China.” He warned that “Japan has resorted to base and shameless tactics, currying favor with foreign powers, conserving its strength, and hoping for a future resurgence,” and expressed concern that China, “out of excessive leniency,” might allow Japan’s ambitions to take shape. Kiyuna emphasized that although the Ryukyus were small, they were crucial to China’s national defense.

This petition was forwarded by the head of the KMT’s Organization Department to Chiang, after which it again vanished without a trace. On March 31, 1948, China’s Ministry of National Defense presented Chiang with an impression of the “Seal of the King of Ryukyu,” provided by the Ryukyu Revolutionary Society as historical evidence of Ryukyu’s ties to China. The ministry also warned that “both Japan and the United States intend to seize this territory after victory,” and recommended that the matter be referred to the relevant departments for further study.

This time, the Ryukyuan petitions finally caught Chiang’s attention. The next day, on April 1, he drafted an order, and on April 2 instructed Foreign Minister Wang Shijie to consider the question carefully.

On July 25, Kiyuna and 16 other members of the Ryukyu Revolutionary Society filed a petition once again to Chiang Kai-shek, who had assumed the presidency on May 20. The 17 “representatives of the Okinawan people” stated that everything in the Ryukyus originated from China and analogized the close relations between China and the Ryukyus to those between a father and a son.

On August 2, Kiyuna arrived in Nanjing. Chiang received Kiyuna on August 9 and, on the following day, the Central Committee of the KMT telegraphed the Foreign Affairs Ministry five proposals that included alleviating restraints on the Ryukyu compatriots in Taiwan and dispatching elementary school teachers from Taiwan to impact the second generation there.

On August 14, Chiang instructed the Foreign Ministry to “study in strict confidence” the Ryukyu Revolutionary Society’s request for China to reclaim the islands. In its top-secret report submitted on August 26, the ministry argued that the Cairo Declaration had not explicitly mentioned the Ryukyus; that the United States, having suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of Okinawa and having built significant bases there, would “never agree to relinquish” the islands; and that the Ryukyus, “poor in resources and impoverished in population,” could not sustain themselves, especially after “seventy years of Japanese indoctrination.” Therefore, neither restoration to China nor immediate independence was feasible.

Despite the Foreign Ministry’s cautious stance, China’s delegation in Japan proved strikingly farsighted. In confidential communications to Nanjing, the delegation argued that the key boundary question concerned whether the Yaeyama (八重山) and Miyako island (宫古岛) should be included within the Ryukyu domain, recommending that China invoke the 1880 agreement to claim both groups. If these two island chains could not be secured, the report noted, “the matter of the ‘Senkaku Islands (钓鱼岛)’ and Chiwei Island (赤尾屿) is likewise worthy of attention.” The same archival file even contains an English-language draft of a proposed “Sino-American Joint Trusteeship Agreement for the Ryukyu Islands.”

Shortly after WWII, the Ryukyuan people repeatedly sought assistance from China, yet their appeals never received open or sustained attention from the international community. Within the Cold War framework, the United States effectively fixed Okinawa’s status as a complex of military bases, rather than allowing the Ryukyuan people to determine their own future.

Under Article 77 of the United Nations Charter, the international trusteeship system applies to: territories now held under mandate, territories which may be detached from enemy states as a result of the Second World War, and territories voluntarily placed under the system by states responsible for their administration.

Furthermore, under the Potsdam Proclamation, the final status of Okinawa should have been determined collectively by the Allied Powers. The 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, concluded with China entirely excluded, with “any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system.” However, the United States never carried out this step. Instead, it maintained long-term unilateral military control and ultimately, in 1972, transferred Okinawa directly to Japan under the label of “reversion,” without any UN trusteeship process and without a formal consensus among the Allied nations.

This trajectory makes one point clear: Ryukyu sovereignty was never conclusively resolved. Rather, it was deferred-submerged beneath Cold War arrangements and political expediency.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of Taiwan’s restoration to China. Ironically, despite Taiwan’s status having been affirmed by the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation, and Japan’s instrument of surrender, some Japanese politicians continue to promote the so-called theory of Taiwan’s “undetermined status.” Against this backdrop, if Tokyo persistently probes red lines on the Taiwan question while simultaneously advancing military deployments in Okinawa, it is hardly surprising that Beijing’s reexamination of the already contested Ryukyu question will draw increasing attention.

The Ryukyu question was quietly placed in a “drawer” of history and geopolitics. When certain conditions emerge, it returns to the center of the table. Today, that drawer has once again been opened slightly. Whether it will be fully opened in the future is not for scholars alone to determine.

What can be stated with certainty, however, is this: Any claim that the question of Ryukyu sovereignty was “long ago conclusively settled” is inconsistent with the historical record, international norms, and the documented negotiations among the Allied powers.

Zhai Xiang works as a research fellow with the Xinhua Institute on China-U.S. relations.

Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a senior journalist with Xinhua News Agency.

More Xinhua propaganda. These propaganda officers from China's state 'news' agency pose as personal 'authors' on Substack, much like their colleague Li Jingjing and others put out videos in her own name rather than CGTN, the state propaganda TV. It's a new strategy of fakery: https://toosimple.substack.com/p/cgtn-and-its-influencer-studios

Interesting that you don’t at all explore what modern Okinawans think about their status, and how polling shows that, while a significant number wish to have more self government, they overwhelmingly wish to remain part of Japan, and far from wishing to join China, the majority of Okinawans view China unfavourably.