Lamenting the Liberal Order That Never Was

Viewing the Venezuela extravaganza from a historical perspective

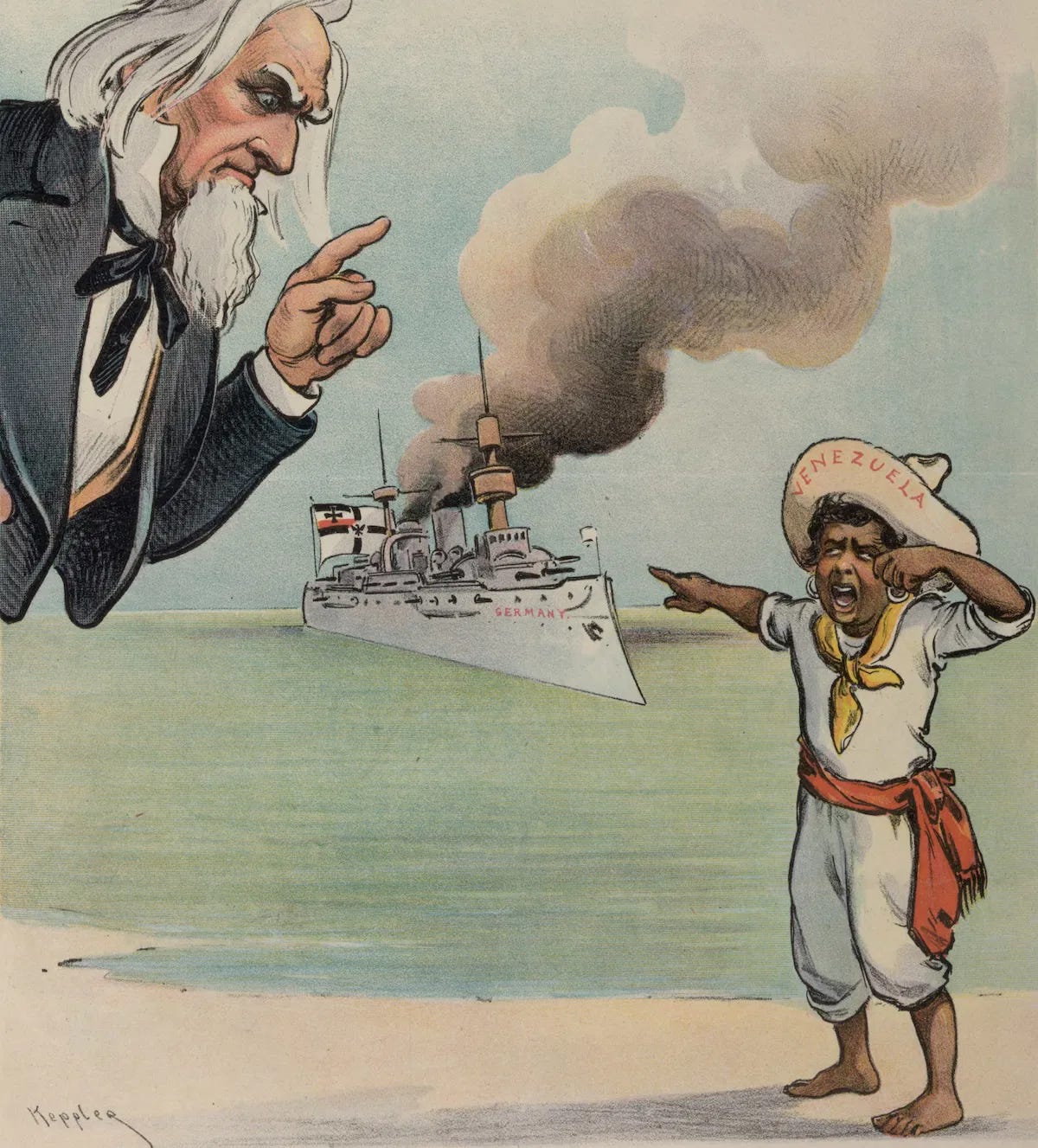

The moment the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine” found its way into the 2025 National Security Strategy, the image of an awe-inspiring blitzkrieg against Caracas may already have flickered through Trump’s mind. For a fame-hungry leader, it would serve as an apt salute to the historic moment over 120 years ago when the Monroe Doctrine, long “aspirational rather than operational” as Graham Allison put it, was finally wrenched from abstraction into action. That shift came with the formal articulation of the “Roosevelt’s Corollary,” in the wake of the Venezuela Crisis of 1902-1903.

At the dawn of the 20th century, it was a familiar tableau: Venezuela in economic crisis, an unyielding strongman in Caracas, and a formidable U.S. naval force conveniently at hand. There was, however, a minor tweak in this historical parallel. President Theodore Roosevelt sought not to topple, but shield the bankrupt Venezuelan government from an ad hoc coalition of European powers poised to collect debts at gunpoint—even though Caracas was then, by Washington’s standards, an outright dictatorship. The successful deterrence backed by sheer military might lent credence to Uncle Sam’s longstanding claim to a sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, henceforth underwritten by direct intervention.

Curiously, the recent capture of Maduro triggered an outpouring of mourning over the unfortunate realignment toward that era of gunboat diplomacy, and the death of the “liberal world order.” Such sentiments are as baffling as they are ridiculous. The successful kidnapping of a national leader from his well-fortified nest was no doubt a living metaphor of power politics, but was it without precedent in the “good old days”?

In a way, Nicolas Maduro only joined the ranks of Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Gaddafi—either captured or killed in the American military campaigns sans the UN Security Council’s sanction, despite UN being the cornerstone of the “liberal world order.” If anything, Trump, compared to his predecessors, has even exerted restraint so far by not destroying the regime altogether. This is not meant as a compliment, but a reminder of the staggering militarization of U.S. diplomacy under Pax Americana.

The “liberal world order” amounts to nothing but an illusory portrayal of the “benevolent” American hegemony. It is Washington’s choosing whether it should act leniently or stringently. The underlying logic has always been power and national interest.

As Maduro was paraded like a barbarian chieftain in a Roman triumph, Trump flirted with the idea of directly running Venezuela with Marco Rubio assuming the role of “viceroy.” Many were outraged by such old-fashioned imperialist moves. Again, they simply overreacted to a template practice inherited from the heyday of the “liberal world order.”

After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Paul Bremer, who triumphantly announced “We got him” following Saddam Hussein’s capture, soon became the all-powerful administrator exercising all executive, legislative, and judicial powers in the country. Bremer was therefore jokingly addressed as “viceroy” by a Shi’ite politician (Mowaffak al-Rubaie, who later served as Iraq's National Security Advisor) in a meeting. Only Bremer, unlike Rubio, had the decency to take offense at the title. Later, it was this “Viceroy of Iraq” who hastily disbanded the old Iraqi military and disastrously plunged the country into a decade-long insurgency and sectarian fighting. Given Rubio’s record of being outspoken despite ignorance, there is every reason to doubt that he would heed the cautionary tale and outperform Bremer.

Therefore, Trump’s inroads in Venezuela do not mark a change in approach to power projection, let alone the end of an era of world order, but rather a recalibration of strategic priorities: from the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific, and now back to the Americas.

Around 2,500 years ago, Athens, the first known democracy in human history, sent an armada of trireme warships to the peaceful polis of Melos, demanding unconditional surrender. While the Melians argued that no state ought to attack another without provocation, the Athenians gave an irrefutable reply: “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a senior journalist with Xinhua News Agency. Email: xuzeyuphilip@gmail.com