How China Spends More Money on Roads than Arms

Deeper look into China's 2035 national road network plan

Last week, China rolled out a once-in-a-decade overarching plan for the national road network. The new roadmap charted another 60,000 km by 2035 on top of the 400,000 km outlined in the previous 2013 edition. It explains how China annually spends 2.4% of its GDP on road construction. To put it in perspective, China’s yearly defense budget, often portrayed as gargantuan to feed the “China threat” hysteria, only accounts for 1.4% of the GDP.

(Note: The portion allocated for state-level roads, the ones outlined in the plan in question, accounts for around 36% of the total road-building finance. The other four levels of roads in China are pertaining to provinces, counties, townships and villages, which take up the rest of the funds and each build and maintain roads in their respective purview.)

China’s road-building drive has recently kept relatively low-profile vis-a-vis the high-speed rail, which has risen to a living metaphor of China’s capacity to expand infrastructure. However, roads are the blood veins that generally sustain the world’s second largest economy. Up to now, three-quarters of the country’s freight transit relies on road trasnportation. And the number of automobiles in China by this March hit 300 million, which nearly doubled in the past eight years. Chinese have been chanting the famous phrase “If you want to get rich, build a road first” since the country began to embrace market economy in the late 1970s, and the infrastructure boom therefore becomes integral to China's success story. Over forty years later, however, nationwide road connections are still far from enough.

This new plan for the national road network, 5th of its kind in history, details every single state-level road that will break ground by 2035. Maintaining the so-called “7-11-18” and “12-47-60” layout for expressways and highways established in 2013, (The three figures refer to the number of radial, north-south, east-west arterial roads) this edition shuns major changes to the nationwide arterial structure, a move that featured the past four such documents. It shows China’s national road building has broken away from the massive expansion approach and entered a stage of elaborate planning. And some new arrangements in the blueprint offer interesting insights into the country’s focus in the near future. This article will help you connect the dots.

(Note: China’s state-level roads have been categorized into expressways高速公路 and highways国道 since 2004. Expressways are tolled, closed-off roads aimed at efficient and fast passage. Highways provide basic, free-of-charge traffic service.)

Cross-Region Balance

Road construction in western and frontier regions ranks high on the agenda. Among the few recent mainstay projects specified in the plan, three are related to these less accessible parts of China: border highways, Sichuan-Tibet connections, overall upgrade of road networks in west China. These efforts reflect China’s long-established national strategy of “coordinated regional development.”

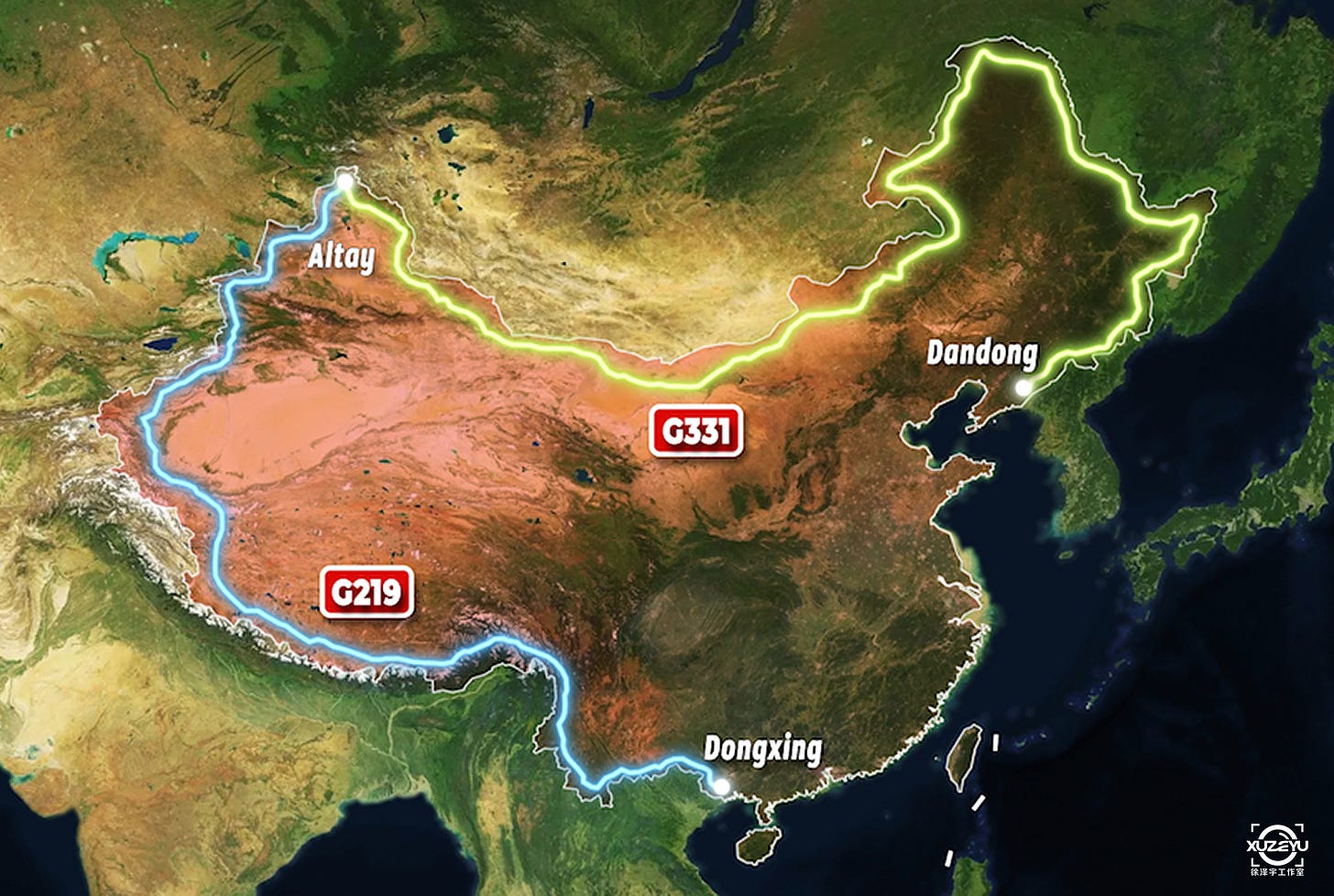

The plan says “the top priority of recent highway construction is to finish all sections of border highways such as G219 and G331.” These two highways stretch along China’s entire land border through some of the most treacherous terrains on earth. The 10,000-km G219, arguably the longest state-level road, runs through most of the frontier areas from the coast of the South China Sea all the way to Xinjiang’s northernmost Altay Mountains. The rudiment of this meandering route was the trailblazing Xinjiang-Tibet road built by PLA soldiers 4,000 meters high on the plateau in 1957, connecting southern Xinjiang’s Kashgar with Tibet’s least reachable Ngari Prefecture. It goes without saying that G219 and G331, yet to be open for passage in all sections, have tremendous strategic implications for both national defense and local governance. And thanks to China’s explosive growth of privately owned vehicles, these two roads also become Internet sensations for an ever-expanding community of self-driving tourists hunting exotic natural landscapes. A booming tourist industry stimulated by these “gateways to the west” will undoubtedly help facilitate east-west interactions and bridge regional gaps.

Road building in western regions is also laying the groundwork for China’s wider ambition to promote Xinjiang into a transit hub reaching out to Central Asia and beyond. During President Xi Jinping’s visit to Xinjiang this July, he said, with the Belt and Road Initiative being materialized, “Xinjiang has changed from a relatively closed inland region to a frontier of opening up.” The new national road network plan vows to “upgrade 70% of highways in west China to level-2 or above.” (Highways are subcategorized into four levels by structural lifespan, design speed and number of travel lanes) And several expressways in Xinjiang and Qinghai designed in the 2013 plan to be “anticipatory lines”展望线 have been promoted to official expressways this time. (Anticipatory lines mean they are designed as expressways but will be preliminarily built as Level-1 or -2 roads because of the low population density and insufficient economic demands. See the explanation by NDRC official) One of such lines based on G315 highway runs from Qinghai’s capital Xining to Xinjiang’s Torugart checkpoint, where the recently announced China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway is likely to enter China. This expressway will knit together all the cities and prefectures in the agriculture-based southern Xinjiang, and provides an alternative to the existing Belt and Road passageway on the north side of the Tianshan Mountains.

New Urbanization

With the absence of change to major arterial lines, a large portion of the newly-added 60,000 km is assigned to meeting the fresh demands from China’s new mode of urbanization. China’s urbanization has been losing speed, and last year the country saw the slowest growth rate of urbanization over the past 25 years. Still, this rate is likely to hit 75% to 80% by 2035 from 64% today. These new developments affected how China formulates new visions for city planning, and therefore road building.

The new plan adds a number of belt expressways in mega-cities and provincial capitals. They are categorized into 12 metropolitan and 30 city belt expressways, which ideas are pronounced in the plan for the first time. They are set to enable China’s recent push for city cluster building. According to the “New Urbanization Plan for the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan Period (2021-2025),” China has set its eyes on a slew of new city clusters other than super-cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Many of them are located in central, west and northeast China, where China aims to forge new economic growth poles. It explains why 8 out of the 12 metropolitan belt expressways will be built in these regions. These beltway projects are set to soothe the prominent problem of traffic congestion going rampant in many cities, and help promote a constellation of social and industrial resources in metropolitan areas.

Another highlight of the plan is the universal accessibility to expressways for cities of over 100,000 municipal residents by 2035. This is a tremendous boost compared to the last edition where that bar was set at cities with more than 200,000. The new scheme basically covers all the 300 prefecture-level cities and quite a few county-level cities. This shows a further inclination for the country to pivot the growth of small cities and counties. The new urbanization plan urges “a change to the growth model of super cities, and solutions to the intractable ‘city disease.’” As big cities like Beijing have already capped the population in the official city planning program, it is imperative to create vigor and attraction in peripheral residential centers to divert the population flow. China also sets up a plan to build “120 model county cities,” which could make much progress once connected to the nationwide expressway network.

Green Focus

What stands out in the plan as something unprecedented is the fact that the environmental protection principles regarding national road building have been made official. It is an echo of Xi Jinping’s concept of “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets.” Considering the surging number of projects in environmentally vulnerable regions, the growing green awareness might generate profound implications for the future mode of road transportation.

A whole new section of the plan includes specific instructions for environmental protection, and requires that “the route selection should avoid all kinds of environmentally sensitive targets including nature reserves and sources of drinking water to the greatest extent possible.” Those that cannot be avoided need to be traversed underground or in the air. Although put in the official guidebook for the first time, this practice has been widely adopted in China for decades. China’s first expressway running through tropical forests, opened for traffic in 2006, set up 18 tunnels to expedite the migration of Asian elephants, an endangered wildlife with a population of approximately 300 in China. Another example is the expressway winding through Shennongjia National Park in Hubei Province which was finished last year. The project cost 1.5 million U.S dollars more to build a runaround in order to preserve two 700-year-old trees, and 85% of the expressway was built in the form of tunnels or bridges to minimize deforestation.

The environmental protection in the plan is further institutionalized with a system of “three lines and one list”三线一单, referring to the red line for ecological protection, bottom line for environmental quality, upper line for resource utilization, and the entry list for ecological environment. The new rules are also meant to curb emission, sewage, noise and other negative effects on environment. The plan explicitly called on efforts to coordinate with the target of peaking carbon dioxide emissions before 2030. Furthermore, the plan mentioned the building of national roads by 2035 will take up an additional 520,000 hectares of land. But it intends to stay clear of as much farmland as possible, given the central government has repeatedly urged maintaining the “red line” of 728 million hectares of farmland.

Road building is one of China’s biggest infrastructure projects, and its planning has the widest-ranging effect on the lives of 1.4 billion Chinese. The 2022 plan for national road network exhibits China’s ambition to build a more balanced, diverse and green economy. This is an incremental process, and maybe one road at a time.

Subscribe to Sinical China for more original pieces to help you read Chinese news between the lines. Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a senior correspondent with Xinhua News Agency, China’s official newswire. Follow him on Twitter @XuZeyu_Philip.

Disclaimer: The published pieces in Sinical China reflect only the personal opinions of the authors, and shall NOT be taken as Xinhua News Agency’s stance or perception.

Why Asian Elephant? Is china not in Asia?

Amanzing peoples !!!!