Decoding China's Updated Reform Roadmap

How the Third Plenum intends to deliver another round of reform benefits

As the pivotal “third plenum” of China’s ruling party just concluded, the meeting’s communique, a concise version of China’s future reform roadmap, has been unveiled for the world to pore over. The 4,000-word document is set to unravel the mystery that has perplexed many China-watchers: Is China’s reform losing steam, or will there be a “big bang” like the first such reform-themed leadership meeting held in 1978?

Both theories turn out a myth. Amid this most transformative self-correction campaign in modern human history, generations of China’s reformers had to surmount the hurdles of their own times to make periodical breakthroughs. As argued by Li Yining, the late pioneer reform theorist, “Reform benefits always wear off over time, and the growth pattern has to continuously evolve when they do.”

As the last round of systemic overhaul under Xi Jinping’s signature “comprehensively deepening reform” begins to take hold, this “third plenum” is now poised to deliver another raft of reform benefits, not just to weather the current economic headwinds, but to revamp the growth model for development over the next five years. Even though a more detailed reform blueprint known as the “Resolution” of the plenum is yet to be published, one would still discover the forthcoming changes, as opposed to the “big bang theory,” will be no less earth-shaking in today’s context, if reading between the lines of the freshly-unveiled communique.

Rural Land Reforms and New Urbanization

“Deepening reform of the land system,”深化土地制度改革 a phrase missing in the 2013 communique, appears in the new reform roadmap, which seems to step it up a notch in the unshackling of the urban-rural dual structure. Over four decades ago, reforming rural land ownership, which basically allowed collectively-owned land to be contracted by individual households, was an impactful move that cracked open a once rigid planned system. Now, another landmark rural land rights reform and the ensuing accelerated urbanization become a new source of growth.

The age-old rural homestead system is most likely to be on the front burner of change. The non-tradable nature of the system was originally designed to protect farmers’ housing rights from land annexation. However, the country’s decades of economic rise and urbanization have seen a huge influx of rural population into the cities, creating a large swathe of vacant property in the countryside, in stark contrast to the saturation of urban land use. As of last year, the size of China’s rural homestead reached 113,000 square km, nearly twice the size of the built-up area in the cities. Once the homestead is available for market transaction, it will surely lead to greater urbanization, higher land utilization rate and bigger economic gains for rural dwellers. It is probably why on top of the “equal exchange of the factors of production between cities and countryside”城乡要素平等交换 mentioned in 2013, the concept of “two-way flows”双向流动 is added to this year’s edition.

Nevertheless, the problems for such rosy prospects remain. The success of the reform hinges upon how to make the rural homestead tradable in ways similar to private property while maintaining its nature of rural collective ownership. China has trod carefully in this area by rolling out a “three rights separation”三权分置 pilot reform of the rural homestead ownership right, qualification right, and use right. The Rural Collective Economic Organization Law, just adopted by China’s top legislative body this June, is also likely to establish parameters for the upcoming “deepening reform of the land system.” Once fully implemented, this landmark reform is set to alter every facet of rural China for years to come.

The communique hails the rural-urban integration as “essential” to Chinese modernization.城乡融合发展是中国式现代化的必然要求 It is yet to specify the precise reform policy of the hukou, or household registration system, but a further relaxing of the restriction is almost certain on the table. As Xi Jinping argued, “modernization for hundreds of millions of rural residents as a whole will unleash enormous creative momentum and consumption potential.” Although China has proceeded with urbanization over the years, there has been an enduring gap of 13 percentage points between the urbanization rate of permanent residents and that of hukou residents (see chart 1). It is estimated that the abrogation of the hukou will generate a 30 percent jump in consumption for the 200 million farmers living in cities across the country. Consequently, China’s middle-income group of 400 million, the world’s largest, will further swell. China has so far abolished the household registration restrictions for those who want to settle in cities with three million residents or less. But a more forceful push is expected.

The “new urbanization”新型城镇化 reiterated in the communique is nothing new, as it already surfaced in the 2013 third plenum resolution. Still, it sets the tone for the model of large-scale rural population migration in the future: non-first-tier cities. In the report to the 20th CPC National Congress, Xi vowed to “promote coordinated development of large, medium, and small cities and push forward with urbanization that is centered on county seats.” The recent policy documents of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s state planner, have tilted towards medium, small, and county-level cities for infrastructure boost. In addition to the land reform and further lift of hukou system, a pivot to lower-tier cities is more likely to ramp up the pace of urbanization, prevent ghettoization in mega-cities, and help revitalize the sluggish property market.

Centralization of Fiscal Responsibility

One of the chief obstacles faced by many cities to push for the “new urbanization” is the fiscal quandary in which local governments have increasingly found themselves in recent years. Issues such as municipal debt accumulation, sluggish land sales and severe imbalance between revenue inflow and expenditure responsibility have dampened their abilities to provide the level of public services needed to achieve “high-quality development.” That is why the section on fiscal reform in this year’s third plenum is a far cry from the one in 2013, which highlighted the matching of fiscal powers and expenditure responsibility at every level of the government. This time, it is set to spawn a “national strategic planning system”国家战略规划体系 in order to centralize more fiscal responsibility and cut the local government’s expenditure.

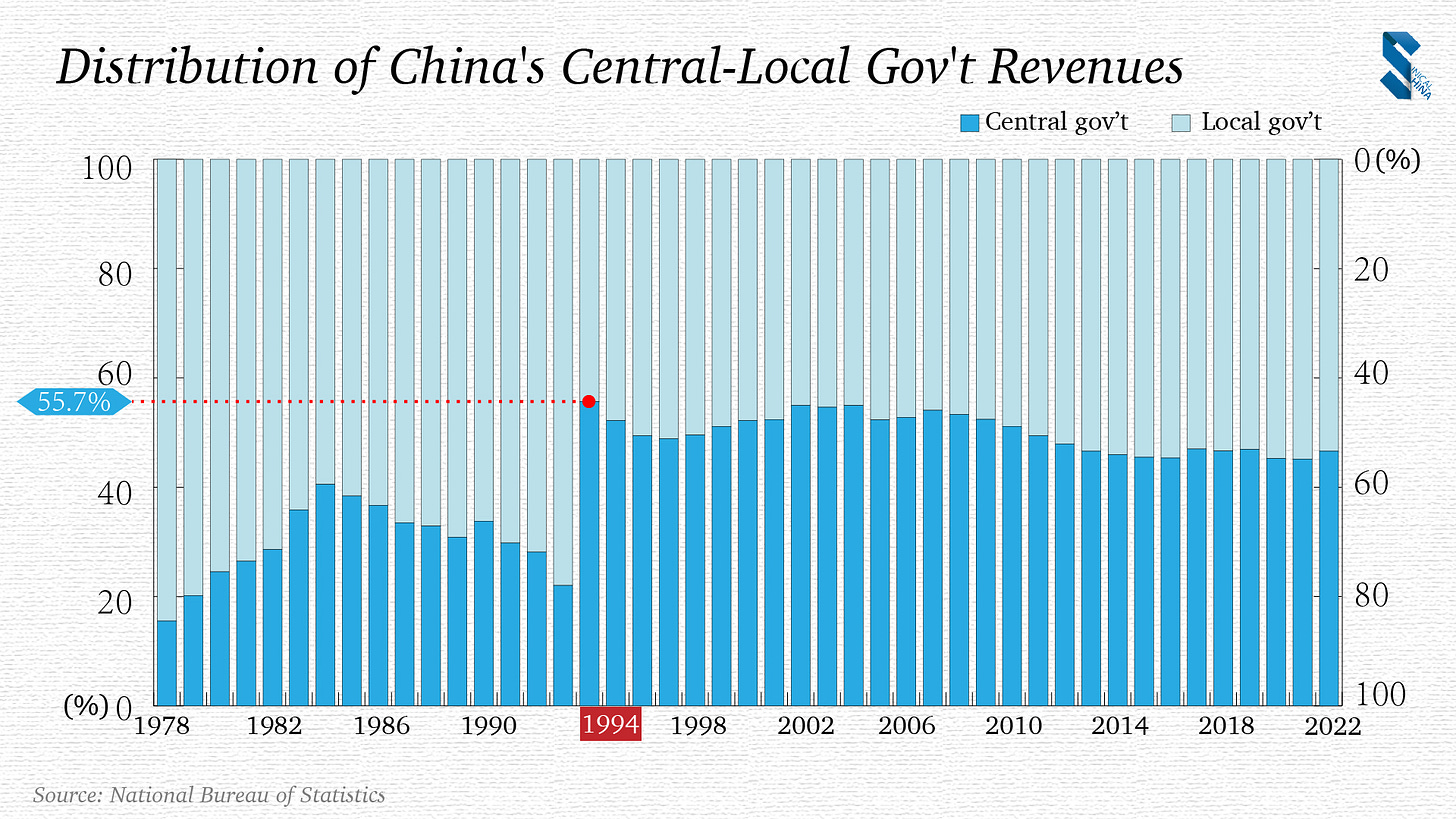

There has been a worrying fiscal discord between the central and local governments. As of 2022, the local government took only 53 percent of the overall revenues, but had to bear the burden of 86 percent of the spending (see chart 2 & 3). The disparity began with the watershed moment in 1994 when China founded the tax-sharing system. It put an end to the “fiscal contracting system” which had separated the central and local budgets since late 1970s, and upended the central-local fiscal power balance that used to favor the latter. As a result, the proportion of the central government tax revenue jumped from 22 percent in the year prior to the reform to 55 percent by the end of 1994, and the figure has been hovering around the same level to this very day (see chart 2).

The problem is that the proportion of local expenditure keeps rising. In 2016, the local government lost a major pillar of its tax income, the business tax. It was replaced by the value-added tax, of which the lion’s share would go to the central government. And the situation has now been compounded by a virtual halt of land sales, which were the main contributor to the local non-tax revenues.

To remedy the issues, the question remains: whether to grant more tax shares to the local authorities, or to consolidate more fiscal responsibilities to the central government. As this third plenum reveals, China is inclined to opt for the latter, laying more emphasis on the “macro planning” to improve the fiscal, tax and financial systems.完善宏观调控制度体系,统筹推进财税、金融等重点领域改革 As argued by the former finance minister Lou Jiwei this July, “China should raise the proportion of central expenditure, and the central government ought to directly manage the affairs that should not have been delegated to the local authorities in the first place.” If the 1994 tax-sharing reform has laid the basis of China’s modern revenue generation system, then today’s reform is set to revamp the expenditure structure. It is not just meant to ameliorate the impact stemming from the property gloom, but also to establish a balanced distribution of fiscal responsibilities between the central and local governments.

Sci-Tech Innovation and Race for Talent

In contrast to the 2013 version which only included one sentence about reforms of the sci-tech management system, this year’s communique devoted an entire paragraph to this particular respect. This came as no surprise as the advance of the “new quality productive forces” was already high on the policy agenda one year before the plenum. But two phrases stand out in the document: “the new system for mobilizing resources nationwide to make key technological breakthroughs”新型举国体制 and “talent.”人才

The “new system” in question has everything to do with China’s sense of urgency to secure the safety of its high-tech supply chains. Eight months after the U.S. launched a trade war against China in 2018, Xi raised this idea for the first time when he met with the team of the Chinese lunar exploration program. The term was subsequently enshrined in various key documents, including the report to the 20th CPC National Congress. A major step to put this idea into practice was made in 2023, when a central science and technology commission was established. It is directly affiliated to the CPC Central Committee, and therefore enjoys much more power to allocate resources nationwide. The next stage of the reform is likely to focus on further empowering this structure, and calibrating it to make breakthroughs in “bottleneck” technologies.

A noteworthy highlight of this year’s document is that the work on “talent” has been raised to a level on par with “education” and “science and technology,” which means that all three are officially recognized as integral to the “basic and strategic underpinning of Chinese modernization.”教育、科技、人才是中国式现代化的基础性、战略性支撑 There were already signs of such a move at the National Science and Technology Conference last month where Xi called for efforts “to adopt a more active, open and effective talent policy, accelerate the formation of an internationally competitive talent system, and build an innovation highland that gathers global wisdom resources.”

As a matter of fact, China’s sci-tech development is closely related to its demographic change. Right before Xi became China’s top leader, the Chinese population dependency ratio started to rise for the first time after decades of continuous decline (see chart 4). Whereas China’s comparative advantage of cheap labor was about to expire, it was in urgent need of raising its total factor productivity, which happens to to the hallmark of the widely-discussed “new quality productive force” featured by sci-tech innovation. Chinese Premier Li Qiang talked about China’s “talent dividend” at his debut press conference. It has to be put in the context that the hiring cost of research scientists in China is almost half of that in America. The plenum document is now indicating that the country must seize the window opportunities to proactively expand its talent pool and sharpen the country’s competitive edge in the sci-tech race. Essentially, the race for future growth is a race for talent.

Subscribe to Sinical China for more original pieces to help you read Chinese news between the lines. Xu Zeyu, founder of Sinical China, is a senior correspondent with Xinhua News Agency, China’s official newswire. Follow him on X (Twitter) @XuZeyu_Philip

Disclaimer: The published pieces in Sinical China reflect only the authors’ personal opinions, and shall NOT be taken as Xinhua News Agency’s stance or perception.